“Film was born of an explosive,” reads an intertitle early in Bill Morrison’s latest and longest film to date, Dawson City: Frozen Time. He is literally referring to the roots of nitrate film stock — gun cotton — but the sentiment lingers on in the notion that film is home amidst the blast wave of human destruction.

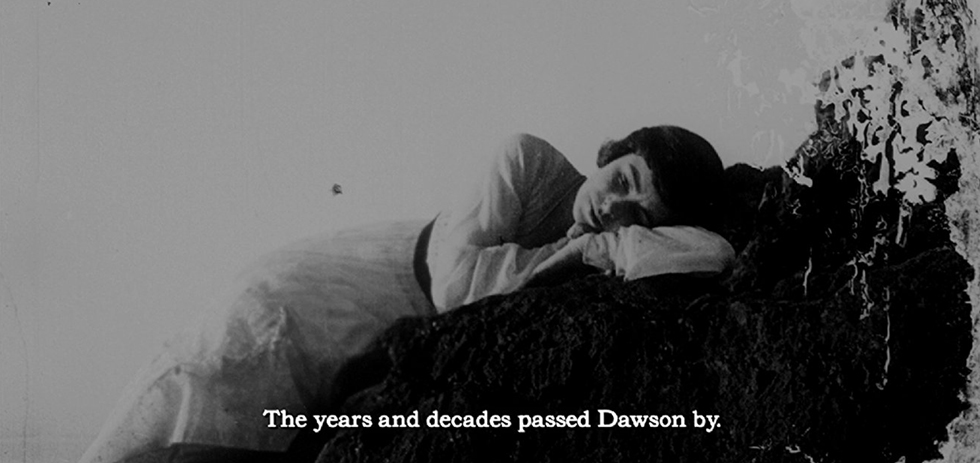

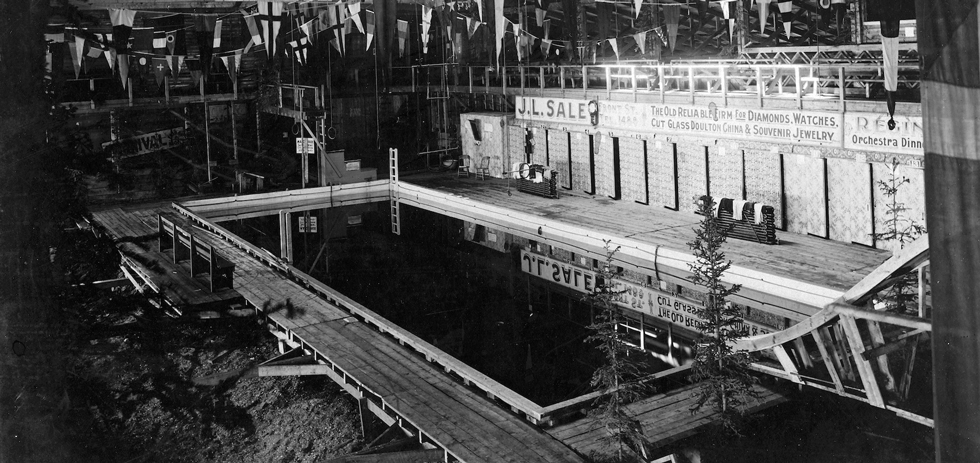

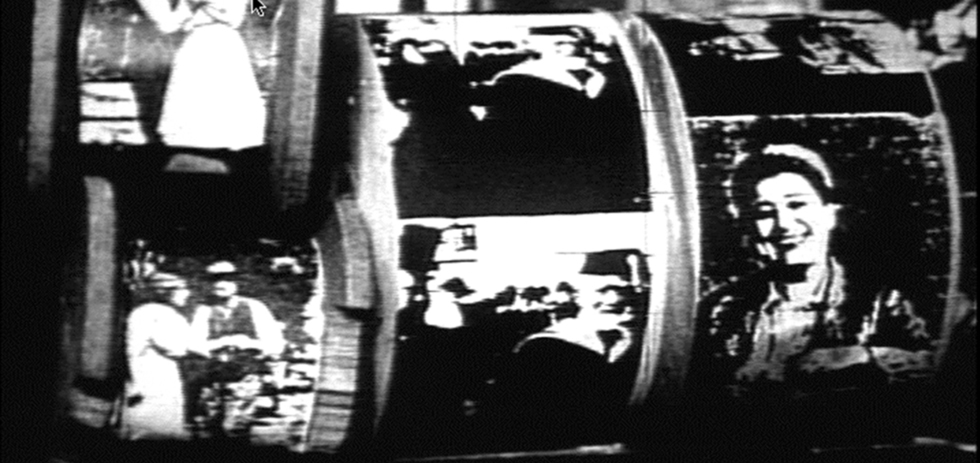

The story of the eponymous Northern Canada town is also one of ripple effects; the documentary begins and ends with an incredible tale: in 1978, hundreds of nitrate film reels were found buried underground in Dawson City, having been stored in an empty swimming pool in 1929. A showing of films long thought lost to time is cause enough for celebration but this initial premise is merely a gateway to Morrison’s real concerns: the rise and fall of American capitalism, as seen through the Gold Rush fortunes of Dawson City. With no voiceover narration (there are brief interviews at the top and tail of the film), the eighty-odd-year tale unfurls through montages of newly scanned nitrate films, the photography of Eric A. Hegg, on screen intertitles and the swirling music of Alex Somers (a Sigur Rós collaborator).

Morrison is best known for his 2002 avant-garde film Decasia, a montage of decaying film footage set to a Michael Gordon symphony. In 2013, Decasia was selected by the National Film Registry for preservation in the Library of Congress. The success of that film has often overshadowed Morrison’s tireless work since. Dawson is one of five feature-length films he has released since 2002, in addition around fifteen short films and three city symphony works.

Ahead of the NSW premiere of Dawson City: Frozen Time at the Sydney Underground Film Festival, we spoke to Morrison about the Gold Rush, late capitalism, and working with archives.

Your film is one of the last to screen here in Sydney at the Underground Film Festival this year, which I think is incredibly fitting, that Dawson City is closing out an ‘underground’ festival.

[Laughs] I hadn’t thought about that. I think of this as my least ‘underground’ film but in some ways, it’s quite literally the most ‘under ground’ of my films.

That’s true. Your filmography bounces around between film festival premieres, musical performances, online releases, conference-specific work. Even something like Decasia, now lauded as one of the most important American experimental film works in recent memory, started out as a live performance.

Well you don’t think about the end point while you’re making it. You’re just trying to make the best film you can for the project. With Decasia I certainly had no idea that it was going to have a life, really even beyond its orchestral premiere in 2001. I was as surprised as anyone else when it gained some distribution and some notoriety. I always thought of it as a very strong film and that I was showing people images they had never seen before but you never know what the zeitgeist or the culture is going to be. At least I don’t.

Thinking less about end points of distribution and more about festival premieres, I saw Jay Weissberg’s name in the credits of Dawson City. Was that related to his work at the Pordenone Silent Film Festival?

With this piece we had in mind a premiere in Venice, rather than Pordenone… in Italy anyway. Venice was the world premiere and Jay Weissberg saw the film in Venice and identified some clips that I had misidentified, or at least they’d been misidentified in the archive. So when we made a subsequent edit we cleaned that up a bit and attributed films to their right authors.

Was premiering at Venice due to some pre-existing relationship with the festival?

Yeah, I would say that. There’s a curator there who’s been following my work and really tracked it from a year earlier and was adamant the year earlier that if it was going to be ready for a Fall 2015 release — which it in no way was — that it would be in Venice. I said “I can’t see it being released in 2015. I figure it’ll be later in 2016.” Over the course of that year, I showed her rough cuts. They were definitely my target festival.

Did that festival premiere mindset impact how you cut the film? It’s quite a break from your some of yout recent work: The Dockworker’s Dream (2016), The Miners’ Hymns (2011), Beyond Zero: 1914-1918 (2014). Dawson City feels different somehow, maybe because of its length or because of its Venice premiere.

Yeah, I mean they’re very different films. I did cut The Dockworker’s Dream silently but it was always intended to be as a collaboration with Lambchop. The other two films you mentioned, those were collaborations with very established musicians as well — Kronos Quartet performing an Aleksandra Vrebalov score in the case of Beyond Zero and Jóhann Jóhannsson in the case of The Miners’ Hymns — and my working process with those, not only did I know who the composer was, I had the first recording of that piece at my disposal to edit with. With Dawson City, I’m really approaching it in a much more traditional way a filmmaker works with a composer and also in the way a filmmaker works with a distribution release. Most of my other films have premiered live with live music before they hit the festival circuit, this was a film-first project, where I used Alex Somers’ music as a scratch track.

You never know how people will respond to the film but I thought it was a very good summation of my work to date, it took a lot of different things that I’ve been interested in and working on and distilled them into one story, so I was hopeful that it was going to have a life beyond the festival circuit and we premiered it in North America at the New York Film Festival a few weeks later and indeed Kino Lorber showed a lot of interest in it and were very aggressive in making sure they had it. We’re still looking for other markets. We have North American, Italy, Poland and Korea and a handful of others.

Hopefully Australia too?

Hopefully Australia, that would be great. It certainly seems to be an Australia-type of film.

It was really well received last month at the Melbourne International Film Festival.

Not bad for an 11am screening, huh?

It’s such a rich film in a way that stops you, mid-festival; there’s so much information, it’s almost entirely silent and it teaches you how to watch the film as it goes on, you get a greater sense of the rhythm of the edit through music loops. It’s a viewing experience that was pretty singular, it’s so much its own piece that isn’t straining to respond to any discernible trends in documentary cinema. What was interesting too, in that vein, is that while the story of the Yukon and the Klondike Gold Rush is immediately compelling, it’s something that has been told so many times before. You seem to be remaking Colin Low and Wolf Koenig’s City of Gold (1957) at points. What comes to mind is the mountain climbing sequence —

Chilkoot Pass.

Yeah, you seem to use the same shots as City of Gold, presumably because of Eric Hegg’s photography, and as a result there’s some overlap in specific subject matter too.

Well, I think the primary text there is Pierre Berton, who is the narrator [in City of Gold]. I think most people who are responding to the stampede are referring in some way to one of his books. So, he’s the source there.

When you were in production for Dawson City, were you aware of the PBS documentary that was being made at the same time? It was called The Klondike Gold Rush and it aired in 2015.

I mean, I didn’t watch it but yeah, the Klondike Gold Rush is, as you say, a well-known subject and certainly a very PBS-type of story, so it didn’t surprise me that it was. When I was working on The Great Flood (2013) there was a PBS documentary about the Mississippi River flood as well.1 These are historic events that shape America in some way and I think I’m coming to them from a different standpoint, or at least, a more visual approach. So it’s not particularly germane to my process to watch what PBS has done.

I watched some of the PBS film earlier this week and I think if you put some of the subjects in common in your film and theirs side by side — the Chilkoot Pass section, for instance — it makes for quite a staggering contrast. You tell the story through specific musical cues and text on screen, which ultimately maintains a focus on what has been captured in these photos. In the PBS film, we see the photos but there’s voiceover and suddenly we cut to an author sitting in their living room in 2015 talking about the book they wrote in 1970. It’s very jarring. This parallel productions trend seems to be linked to a collective need to look back at specific events at specific points in time. I know in the past you’ve spoken about how The Great Flood responded in a way to Hurricane Katrina. What do you see Dawson City responding to, then? Late capitalism and the erosion of American labour relations?

Both of those, yeah. I struggled with whether I was going to include [Donald] Trump’s name in my documentary for an early part of the edit until last summer when it was clear he was in the [general] election and, though I was blind to it, had a good chance of winning.2 At one point I said “Okay, I’m going with this part of the story” because you don’t want to include that guy’s name in your film if you don’t have to. I do think that that story has bared out. You know, in some ways the story of Dawson City is a microcosm of the development of North America. When you look at the removal of indigenous people and then the co-opting of small labour by big corporate and mechanised labour and the lack of a union in the mines… the Earth has basically been raped by these corporations.

The story is a condensation, 100 years taken as a whole, in North America. I think that’s clear. I also think that there’s parallels, for instance a reference to the Wall Street bombing in some ways parallels the 9/11 attack, both literally in terms of location but also in the greater themes of anarchy. You also look at the footage of the silent protest of 1919 where you have African Americans basically demonstrating against mob violence elsewhere in the country, an issue 100 years later we still unfortunately are dealing with. So I think America was built on some pretty serious fault lines. You could make a greater case that capitalism was built on the same fault lines. Dawson City is a distillation of that story. You can see it as a simple story of how some films were buried and retrieved but it also encompasses a greater story of the history of Western civilisation.

I think my favourite stretch in the film is when suddenly it becomes very apparent that your focus is on labour relations. It begins, I think, with the striking miners and the national guard opening fire on them —

The Ludlow Massacre of 1914.

Up until that point you’ve given us the gold rush story, we’re thinking about the Yukon, Charlie Chaplin, the origins of Hollywood and personal histories and then suddenly it becomes very pointed. You stop with the focus on individual fortune and show us how the fortunes of America’s national pastime (baseball) is intertwined so intimately with the massacre of a group of striking miners.

I’m glad you picked that up. The Black Sox scandal is intricately related with the union material.

The specific footage too, the failed double play in the 1919 World Series, acts to almost chastise the viewer. You’re so aware of the pleasures in seeing this infamous sporting moment on film but you’ve set up the context in a way that these images can’t help but be seen as a response to the oppression of labour. There’s a great personal link, too, with the famed anti-labour judge who goes onto become the first baseball commissioner, Kenesaw Mountain Landis. He’s the closest you come to having a villain, he’s the embodiment of evil in Dawson City.

By the time you finally see a visual of him, a moving image of him, he looks like this soulless person.

It’s chilling, though not at all unexpected, that at that time in American society the solution to a labour crisis was to stamp out the rights of laborers. That’s something that I feel is echoed today.

Yeah, I think that traditionally, that the powers that be use a small infraction to implement these huge overarching reactions, whether it’s 9/11 so let’s now spy on everyone’s cellphone conversations, and that’s just an example – there’s always some sort of small thing. That’s why these conspiracy theorists will say that it was a plant or it was encouraged by management so that there can be a law that overreaches and denies you whatever civil rights you would have had.

The way you use footage, in some respect, liberates these narratives. I love that the Pathé newsreels suddenly become your weapon — what was essentially ‘this is our version of the news’ becomes ‘this is my version of history’. What’s striking too, is how you engage with the depiction of Canada’s First Nations people. There is this assessment of the way indigenous people were captured in front of the camera. This is also present in Decasia: a lot of the source footage comes from ethnographic films made as part of colonial studies. In both that film and this one, the filmed image is itself a colonial conquest, where indigenous identity is taken or commodified by film. In Dawson City you end on that point, that this indigenous population who have been relocated and subjugated suddenly become the subject of tourism — they are living history that can be marketed.

Chief Isaac was a remarkable guy because he was sort of zen in his acceptance of this invasion. He was like “Okay, this is happening, for better or for worse – for worse. There’s no way we can turn back the hands of time and the best we can do is to try and help these people from themselves, from the element, they’re babes in the woods here.” He became a very important ambassador, navigating indigenous relations with white people, and also a great local hero. So he did become commodified, though not without his own consent. This was a guy who would stop by the Dawson Daily News and let them know there was something in the paper that bothered him. He was really a part of the community, he was a very remarkable individual.

One of the really touching things about this whole research that I did was that Library and Archives Canada alerted me to the fact that there was this… what started out as a home movie, amateur footage of this trip to Dawson City in 1925 that was then bought by a travelogue company and released a few years later but his tribe had no idea there was this existing motion picture footage of him so when they got repatriated to the Yukon Archives and then they had a screening for the Hän people that was a very emotional evening, so I’m really glad that that stuff is accessible now because he’s sort of lived on as just the photograph that you see twice [in Dawson City] — in 1895 as a 40-year-old chief.

Your films exist as miniature archives on their own. Are you conscious when you are editing or when selecting footage that in forty years this film might be the key moving image text about a historical moment in time? That Dawson City might be what people look to to better understand the Yukon Gold Rush?

I tried to get it right. I tried to be very accurate, knowing that it was a story that has been mistold so many times. It’s amazing to me how many people still place Dawson City in Alaska. You just read that over and over again. Even after watching my film, synopses are still calling it Alaska when I am screaming “Canada” at you three times in the first 90 seconds of the film. So there has been a lot of misrepresentation associated not just with the Gold Rush but also with Dawson City. My sort of true north here was that God was in the details; the more details I could include, the more it became an epic, overreaching story that had some sort of universal reverberations.

I’ll always remember when I first showed an early draft of the film to my sister, there’s a moment where Walter Troberg is identified as the captain of the hockey team in 1922 and she was like “Okay, where are you going with this? You’re spinning out on details.” But, you know, he comes back, his family ends up owning the Dawson Amateur Athletic Association (DAAA) before it burns down, so there was this belief that by trying to tell the story as detailed and as accurately as possible, that it would reflect a greater truth.

I haven’t thought about where it’s gonna sit in the pantheon of Gold Rush stories but I was aware, especially when I met the Gates [archivists Michael Gates and Kathy Jones-Gates], that Ridley Scott had made a Klondike movie [the 2014 miniseries Klondike] that they just hated and all their friends hated and everyone in Canada hated, from what I could tell. I was thinking ‘Oh, if Ridley Scott can’t get it right…’ People are looking over my shoulder here, the Gates being, pardon the pun, the gatekeepers. They did not suffer inaccuracy. There was going to be no poetic license here. I knew I had to get the story right. Really one of the great compliments I got was, after showing the film in Dawson, the head of the Dawson City Museum said that that first thirty minutes was the best telling of the Gold Rush that he’d ever seen. So that meant a lot to me.

That marks an interesting shift too, in terms of accuracy, from some of your earlier historical work. I’m thinking here of The Film of Her (1996), where you tell the story of Howard Walls but he’s unnamed and there’s a slight a re-imagining of the people and events within his life.

I’d always pitched Dawson City as a longer version of The Film of Her. I very quickly realised that because this is such an incredible story, if I start fudging the facts it becomes a slippery slope down the Chilkoot Pass, if you will. There are so many incredible facts here — it all has to be believable or none of it is.

I’ve read that you made a follow-up to The Film of Her in 2016 called Niver vs Walls but I can’t find any information about it being released?

Yeah, it’s yet to have a world premiere. So if anybody out there wants to see Niver vs Walls, there hasn’t been a lot of takers.

I think a lot of moving image archivists would be pretty interested in it.

That’s true. It was made for the Orphan Film Symposium. So I shouldn’t say it hasn’t had its world premiere because it did screen there. It hasn’t as yet shown in a major festival but maybe there’s some festival of moving image journalists who would like to see it.

A lot of your early film work is freely available online — you just put these films on your Vimeo account. A lot of performance-specific works, too. The collaboration you did with Lambchop, The Dockworker’s Dream, is available on their YouTube account in 1080p.

Yeah, I mean that was a project made with a great spirit of collaboration. Not just with Lambchop but also with the Portuguese archive [Cinemateca Portuguesa] and the presenting festival, Curtas Vila do Conde. The festival director met Kurt Wagner and I at a festival and asked us if we wanted to do a live performance at the next Curtas and we said “Sure.” Basically there was no money, so we said “You’re gonna have to get us into the Portuguese archive and release that footage and, in the spirit of collaboration, Kurt’s gonna make some music and I’m going to select and edit some footage and we’ll call that a piece.” The benefit for me is that I got a new film and Kurt had a promotional piece for his new record. It was singular in that it became an eighteen-minute music video, in a sort of way. Ryan Norris made the track that is essentially the music and Kurt sang on top of it, and did the lyrics. It was was a joint collaboration with them.

For Dawson City you’ve collaborated with Alex Somers, who scores the film. In an interview he did with the CBC he said you told him that the feeling of the music should be “Northern”. That reminded me of Glenn Gould’s The Idea of North, that unattainable, murky idea of what the ‘North’ is. What exactly did you mean by “Northern” when you were talking to Alex?

Well, I do describe what he ended up doing and what Sigur Rós does as ‘Northern’ and I just came back from a week in Iceland and there is this vastness. I don’t know if you can characterise that as ambient or ethereal music but there is not a lot of beat interrupting this epic swirl. Michael Gates said that he thought that I captured some sort of sense of the North and I think that’s, from his perspective, also the historical accuracy, the dryness of it — there’s not a lot of grandstanding. In Alex’s music, I know the one instruction I certainly gave him was that I wanted it to read more as a tragedy; there was this incredible silver lining about the demise of this town, or perhaps the demise of Western civilisation and there should be an inexorable death knell. It’s so hard to talk about music but I thought he would know what I meant. Certainly we went back and forth quite a bit. He gave me something that probably will sound like his next solo record, and I had an entire excel spreadsheet of cues and notes – “No, no, no, yes… let’s talk about the yes”. It was a very fruitful collaboration in that way.

I didn’t know a lot about Alex. I knew the 2009 record he did with Jónsi, Riceboy Sleeps, so that became the scratch track. The two of them wrote three or four tracks, about twenty minutes of music that I cut to to begin working, and when that ran out I put on Riceboy Sleeps and when that ended I started on those three or four tracks again. When he started working he removed everything that I’d been cutting with and basically started over. That really informed the edit because there weren’t any hard beats, there was nothing that I was cutting to, per se, there were these swirls and flowerings of sound that demarcated movements but everything sort of happened as a part of a swell, for lack of a better description. Maybe that’s what Northern music is.

I doubt this was intentional but when I watched The Film of Her I noticed that part of the music in that, the third movement in Henryk Górecki’s Three Olden Style Pieces, is quite similar to some of the Dawson City score.

I think you’re right. There’s no question that Alex was inspired by Górecki, most modern composers are. I used that piece twenty years ago, as did three or four other directors in that time, I’m rather embarrassed to have used it at this point but it is a great cornerstone of late twentieth-century cinematic music.

Another collaborator you had on Dawson City, which brought me great joy to see in the credits, was Galen Johnson, who did the title design. I know you and Guy Maddin have a mutual appreciation for each other’s work. How do you feel about his approach to the notion of a cinematic archive?

It’s just jaw-dropping. He’s so amazing. The Forbidden Room is just an astounding piece of work. There’s a scene in the Thanhouser film The Girl of the Northern Woods which I use briefly in Dawson City to illustrate the Gates’ romance, they’re walking through the woods and then there’s a surveyor who’s laughing. Anyway, there’s a scene where somebody rushes into a campfire and tells them that somebody’s missing and they all go rushing off. The camera set up is exactly like a scene in The Forbidden Room so when I discovered that film I sent it to Guy and was like “Look at this!”. He channeled this 1910 film without ever having seen it. He flipped out.

Strangely, Guy and I have been aware of each other for over twenty years, pre-dating either of our celebrity, his actual celebrity and my quasi-celebrity. Our paths were crossed through a mutual friend who lived in Winnipeg, he had VHS copies of my work and turned Guy onto it a long time ago. We sort of show each other work or talk about work that’s inspired us. I find in him a great kindred spirit but, like you say, he approaches it in a completely different and such a marvelously humorous way. It boggles my mind, what he does. When I heard about the hockey rink [in Dawson] and how the nitrate stuck up through the ice and how there were kids stealing it and setting it on fire, this was like, ‘can I get Guy Maddin just to shoot that scene?’ We’d have children lighting films on fire as they were trying to play a hockey game, or there would be a bulge in the ice that they had to work around. It all sounded like a fantastic Guy Maddin story, so I told him about those plot points early on.

When I saw The Forbidden Room I was really taken by the titles. Guy, Galen and Evan [Johnson] were at Tribeca and I approached Galen and said “I’m working on this film and I need titles, let’s talk.”

Have you seen their new film together, The Green Fog?

No, I haven’t.

Are you familiar with the premise?

No.

It’s a remake of Vertigo, scored by Kronos Quartet, and entirely made up of found footage of films and television episodes set in San Francisco. It reminds me of The Spark of Being (2011), your found footage adaptation of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein.

That’s great, I have got to see that.

I know that you have re-used a select group of shots throughout your films. In Dawson City and The Film of Her there’s a shot of the plastic of film being made —

The Romance of Celluloid, 1937.

…there’s a shot of sprockets being punched into celluloid in The Film of Her that’s also in The Death Train (1993). For you, are there these go-to archival works or are you intentionally nodding to your earlier work?

I think between two films that were relatively close together — The Death Train and The Film of Her — it was a sort of shorthand. It was my vocabulary that I was already using. And again, I see Dawson City as a wide-reaching distillation of a lot of different subjects I’ve been interested in over the years and it sort of became this catch-all. I think Dan Streible, again of the Orphan Film Symposium, suggested I go back to that source material, the MGM film The Romance of Celluloid, because it’s such a visceral look at the manufacturing of film. It’s also a frightening film in its racism. I don’t know if you’ve ever seen it but it starts out with African Americans picking cotton, it calls them ‘darkies’, and then shows us these beautiful white people on screen at the end. Just really jaw-dropping. That aside, it is this incredibly beautiful footage of the making of nitrate film at a high-end industry standard. Because I was approaching the ingredients of nitrate, the gun cotton and its military applications, and this stuff as a vehicle for memory and history, it seemed really important to go back to the actual source and re-scan it at 2K, as opposed to whatever I used in the mid-1990s.

I read that you have your own scanner, or an optical printer?

I had an optical printer back in the day that I used but, for instance I’m not licensed to have nitrate film in my apartment so there’s a lab in Maryland, Colorlab, that now they’re pretty adept at whatever I want to throw at them. Takes a few months but I can send them something pretty funky and they soak it, get it loose and scan it. So they’ve been really valuable collaborators.

In that vein, your films often test the limits of institutions. For Dawson City, Library and Archives Canada were testing out their Scanity 4K scanner. Was that process a case of you selecting things for them to scan?

It was just incredibly fortuitous but it was also part of knowing that thing was going to be installed was the lightbulb moment where I realised I could make Dawson City now. This is a story I’ve held in my sock draw for a couple of decades, knowing that I could tell it differently than anyone else could tell it and I’m grateful that no one really told it at all in that time. When I met Paul Gordon in Ottawa he was the programmer for the Lost Dominion Screening Collective and they had invited me up to show Decasia or The Great Flood and he mentioned that his day job was digital migration at Library and Archives Canada, so I was like “You have Dawson City, then.” He said “Yeah, we have Dawson City.” I asked whether we could get HD or whatever and he said “Well, we’re gonna have a 4K scanner installed in January.” Knowing that no one had scanned the Dawson material at any resolution — maybe there’d been a Standard Def video — my workflow is going to be very streamlined. Paul became and still remains an incredibly great inside source up at Library and Archives Canada, who can turn stuff around in an incredibly short amount of time.3

They’re very proud of their Dawson collection up there. In some ways, it’s emblematic of their entire archive, so it wasn’t a big stretch to think that that would be some of the first stuff that would get scanned and eventually would all be scanned. So the sooner it made it into their queue, the better. They just happened to have a client who was looking into the entire database: “Let’s see that Edison, or let’s see that Thanhouser,” stuff that really nobody was looking at. I mean, it’s not their job to look at it. I’m convinced that a lot of that footage people hadn’t seen before, that no one alive had seen before.

You said that the story of Dawson City was in your sock draw for decades, does this mean that you came to the film with some editing framework or structure already in mind? Did you have a version of the film edited in your head?

No. I didn’t really know the story. I didn’t think it was in Alaska but I thought it could have been some private swimming pool… It always was such a fantastic story. What was a swimming pool doing in the Arctic anyway? It was always just a phenomenal believe it or not story but also a story where there was an associated enormous collection of rights-free footage. At the same time I was thinking of making The Film of Her I was aware of Dawson City and that that story could be told in a similar way. You could use the footage and the supporting footage to tell the story. Again, I’m glad that I waited.

How do you feel about the incredible story of your new film, the Icelandic discovery of Russian film reels in the sea?

In Iceland I got to interview not only the archivist who now houses those four reels but also the fisherman aboard the ship where they pulled up the film. I like to say that instead of finding a needle in a haystack, I find a needle and then build a haystack on top of it. I think that’s what happened with this story. While I was finishing Dawson City I was thinking to myself ‘Now how much more can I really say about archival film after this? Haven’t I said what I need to say at this point?”. Then Jóhann Jóhannsson wrote me in July of last year and said “Look at this amazing story!” and then all of a sudden this became a film that Jóhann and I could work on together, that had an Icelandic root.

Like Dawson City, this was like “How the hell did four reels get into a lobster trap?” It’s hard enough for a lobster to get into one. Because of this last trip I understood that they were trawling the bottom of the ocean and it’s not just film reels that show up there but bombs and pieces of ships and whatever has drifted to the bottom of the ocean. These particular four reels have sort of melded together; the reels themselves had rusted away to nothing, as had any core that had bonded the films and they were kind of rusted as a cylinder, a donut, and found themselves into a trawling that way.

The Village Detective, which is the translation of the [title of the] Russian film from 1968, stars Mikhail Zharov, a Soviet-era film star unfamiliar to virtually anyone in the West, from what I can tell, but well known by almost everyone in Russia. I don’t know who we could compare him to but he is much beloved as sort of a bad guy, so Edward G. Robinson or something. Warmer than that. Not a gangster but your prototypical older era Soviet guy who played the uncle and who probably was a little drunk and made old jokes from the last generation. Mikhail Zharov made 66 films, starting in 1915 and pre-dating the Russian Revolution up until the trilogy that The Village Detective is the first part of. His career ended in 1978, so it basically spans the entire Soviet era. He is, in some ways, the Soviet cinema man: he was in an Eisenstein film, he won two Stalin awards and he was also blacklisted by Stalin. So he is an interesting character and, in a way, I am also a village detective. It’s a good title. Thinking about how a haystack could be piled around a needle, it’s an incredible third act, that here’s this long arching filmography that spans the Soviet empire and then it’s found at the bottom of the North Atlantic Ocean twenty miles off the coast of Iceland in 2016.

Now you’re in the business of making films about dying empires of the modern political world.

[Laughs] It’s like “If you thought capitalism was bad, look at what happened to communism!”

Another great disaster, one you alluded to earlier, is the impact of humans upon the natural world. You’ve often cited Godfrey Reggio’s Koyaanisqatsi (1982) as important for you in envisioning a non-narrative cinema. What films since Koyaanisqatsi have had that same impact on you?

Well, that was sort of the a-ha moment for me, and also the use of music. There’s a lot of non-narrative cinema that doesn’t use music in the same way. I think I had the great fortune of studying under Robert Breer at Cooper Union and so I was introduced to, especially the American avant-garde and experimental film, and that really informed a lot of my early work, Ken Jacobs, Ernie Gehr and Stan Brakhage. Coming up from that I found documentary rather late in life, when I realised that as documentary became more of an expansive genre, one that could be understood by a larger audience under the rubric of documentary but you also had a lot of flexibility of what you could include and how you could tell the story. That became, at times, a more forgiving and more stringent genre to associate myself with. I much prefer to think of myself as a documentary filmmaker than an experimental filmmaker.

There was an Alan Renais film called Toute la mémoire du monde (1956) about the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris and I think that was highly inspirational for both The Film of Her and Dawson City. The idea of telling a dry enunciation of facts and stats and in some ways telling a more metaphysical story while on the surface just telling the straight narration or examination of a building and the way it works. He was in some way comparing a library to human souls. Lyrical Nitrate [dir. Peter Delpeut] was an enormous inspiration. The use of archival film and its materiality as, again, a manifestation of spirituality. I’ve probably named all those before but they were the key moments for me.

Dawson City: Frozen Time screens on 17 September at the Sydney Underground Film Festival.