Donald Trump’s 2016 presidential campaign was propelled by the part-slogan part-policy to “build the wall!”. While the plan was controversial (and logistically tenuous), the most tangible split from existing US policy was in the spectacle, of announcing that a wall would be built and that Mexico would be picking up the bill.1 34% of Americans supported Trump’s declaration of a national emergency to “build a wall on the US-Mexico border”, however, the same ABC News poll from April this year found only 27% of Americans supportive of making the process for undocumented immigrants requesting asylum easier. Borders, immigration and ‘defence’ have been enduring obsessions shared by the majority of America’s political class and a loud fraction of the country’s population – regardless of party. Bill Clinton endorsed the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigration Responsibility Act of 1996, arguing that it strengthened “the rule of law by cracking down on illegal immigration at the border.” Obama signed a $600 million billion to increase Homeland Security’s funding.

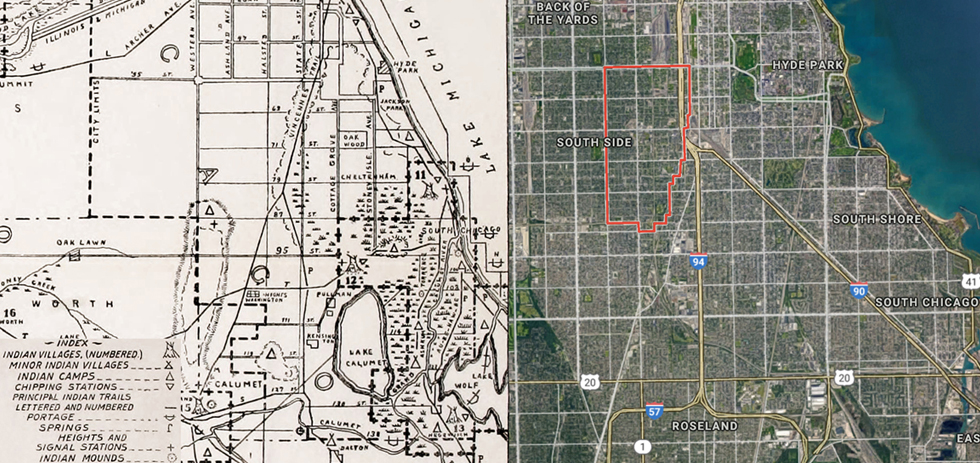

The obsession with ‘the border’ and ‘immigration’ in the United States is echoed in the country’s urban centres, where formal walls and barriers are exchanged for markers and signifiers: the physical interventions of parks, crossings, intersections, rivers and infrastructure; the social in a reduction in emergency trauma centres, hospitals, schools and affordable housing.

Chicago, the third most populous city in the United States, has the highest number of Black or African Americans in the country. It also stands as one of the most segregated cities in the United States of America. In the neighbourhood of Englewood, the black population is 98.5%, against a 0.6% white and 0.4 percent Latino population.2 There’s no wall or border around Chicago’s South Side, although the structural barriers entrenched in the area over the last several decades have been just as effective.

Huddled under umbrellas on an overcast day, a group of about twenty Chicagoans are facing down the sounds of passing traffic – car horns, sirens, shots – in prayer “for all the families and all the communities who have lost a loved one to violence and injustice in any form.” However brief, this scene on the corner of the intersection of West 63rd St and South Pulaski captures the sense of tension and uncertainty underpinning day-to-day life on the South Side, as well as the resilience of those living in the area. This image is succeeded by similar scenes of life in Englewood, flashing past on screen with similar haste: a testimonial on the fear of raising a child in the area, and a man arguing with a group of white police officers wearing blank expressions – “How many white communities got mostly black cops? None of you motherfuckers – nowhere!” Each of these snapshots coalesces into the confronting yet resoundingly humanist community portrait in George Gittoes’ latest documentary.

White Light flows at a more frenetic pace than Gittoes’ previous films – his last outing, Snow Monkey running just short of 3 hours – with frequent cuts echoing the volatility and impermanence of life in South Side. Centred in Englewood, the film locates itself in May Block, with the block’s community leader Smiley doubling as the narrator of the film. Characters reflect on being shot, losing loved ones, as well as the broader social and psychological effect they’ve experienced: living within a community in a perpetual state of mourning, maintaining a resolute sense of determination despite it.

White Light doesn’t seek to position itself with a constructed, apolitical and analytic distance. Instead, like the bulk of Gittoes’ documentaries, it sets out to establish intimacy and prompt empathy. Local rappers and beats are paired with a range of session musicians from fields as far flung as jazz and metal under the coordination of White Light’s Music Director Hellen Rose, echo the contrasts within the world Gittoes seeks to capture. The film captures the tragedy of gun violence without severing the incidents from the roots or structures responsible for its prevalence; we watch scene after scene of community members articulating how they perceive police as a great of a danger – if not greater – as any gang member.

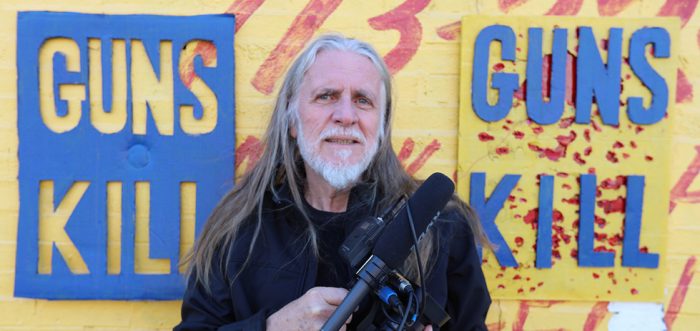

White Light serves as the Gittoes’ latest examination of the American psyche, that he began in 2005’s Iraq-based Soundtrack to War and continued in Miami, Florida with 2006’s Rampage. At 69, Gittoes is yet to show any signs of slowing down. We caught up with George at his home last month, as White Light screens at Brisbane International Film Festival.

On paper, White Light isn’t exactly the film you’d expect a 70-year-old Australian documentarian to make out of the blue, but in the context of your greater output, it makes a lot more sense. Love City Jalalabad sprung out of Miscreants of Taliwood, while Soundtrack to War – which focused on soldiers in Iraq and their relationship to music – introduced Elliot Lovett who, alongside his siblings Denzell and Marcus, sat at the heart of your following documentary in Florida, Rampage. The rap battles in Soundtrack to War and Elliott also played a part in you going to Chicago to shoot White Light, right?

Elliot was a genius, and was one of the soldiers that created freestyle raps about the experience of the day, and that’d help them, psychologically, to avoid post-traumatic stress and stuff. At one point I said “Elliot, you’ve been on 200 combat missions, this is ridiculous. I’m going to talk to your combat officers and see if I can get you … better, softer duty.” And he said, “George, it’s more dangerous for me in Miami.” I’ve told that story many times but [another soldier in Soundtrack to War] Yonas, who’s Ethiopian-American, he’s black, he laughed and he said, “Oh, but Miami’s nothing, man. Chicago is much more dangerous than Miami.”

You shot Rampage in Miami in 2006, but have remained in touch with the Lovetts?

Originally, I was going to go back to Miami and shoot a sequel depicting 10 years on. But then when we were there, we had done such a thorough job that I realised, “I don’t need to do a sequel. I’ll do a recut. I’ll just give a new end.” And if you watch the film today it’s much, much stronger because it really is about this thing of not compromising. They’d rather be poor than sell themselves out. It’s about not selling yourself out.

With Denzell, really, he didn’t get his deal because he wouldn’t compromise, you know? As you see in the film, all the top people said he’s a genius but that he’d have to do material like Lil’ Bow-Wow, stuff that was age appropriate. And he just wouldn’t compromise. Anyway, I got the news a couple years ago that he’d been shot, and I immediately went to see him and in Rampage, Swizz Beatz says, “You’ve had a much more real life than 50 Cent except that you haven’t been shot yet.” 50 Cent was shot. Well now, here I turn up just after Denzell’s been shot, and his brother Marcus was really killed because he wasn’t a very professional gangster, you know, like these really hard people that survive, like Bully T and Rampage. The Lovetts are pretty soft. And so, with a bit of luck, I’ve got Swizz Beatz looking at the film now and Alicia Keys and people like that. Like, maybe it’ll happen for them now years down the track.

Denzell was shot with an AK-47 and I went back with Denzell to where he it had happened. He explained that he died and the paramedics came. His heart had stopped, and they got a defibrillator, which you can put on a heart. If it hasn’t been too long, they can bring someone back to life. While he was dead, a true poet, he wrote a poem. When he was clinically dead he wrote a poem called “White Light.” And then as he regained consciousness he remembered it, so he kept repeating it to himself in the ambulance so he wouldn’t forget it. And I thought, “Well that’s a great film.” I recorded him talking about it and that’s where the name “White Light” came from.

There’s a lot of these threads between your documentaries, where the figures you meet will have some link that carries into a later film. There’s the example before of Soundtrack to War and Rampage, but how did Yonas’ retort eventually lead to you heading to Englewood to shoot White Light?

I stay in touch with all the soldiers from Soundtrack to War. They see me as a kind of a father figure. Most of them are kind of lost boys, have never had real fathers. And Yonas, through Facebook and everything, saw that I was down in Miami and once again he said “George, this is not fair. You made Rampage. I always told you should come to Chicago.” And so I made the decision, “Okay,” we’ve done the recut and so we went to Chicago. And I was expecting it to be packaged for me by Yonas, that I’d get there and he’d have all the right people for me to meet and everything else. But since Iraq, Yonas has become a multi-millionaire. He owns about 23 Dunkin’ Donut franchises. He’s even gotten married and while she’s very nice, she’s terrified of anything to do with ‘the Ghetto’, with guns and so on. Suddenly when I arrived she said “No, Yonas. You’re not going. You’re not going to work with George, it’s too dangerous. You’ve got children now.”

Yonas and everyone else said, “You’re going to have to get someone with a licence to carry,” meaning a gun-carrying bodyguard, “and you’ll have to live outside of the hood,” you know, in Englewood where we were, “and just travel in.” I knew that wouldn’t work. In all the war zones I’ve ever worked in, I’ve always been in the heart of Baghdad or Bosnia, in Sarajevo. So Waqar and I went out, got a local newspaper. We worked out where the worst, the most notorious gangsters – the Gangster Disciples – were and said, “okay, we’ll get a place in Gangster Disciples country, in the place where there’s the greatest number of deaths.” We got these two apartments on an apartment block which is mainly populated by groups of gangs who’ve got guns and ankle bracelets and drugs and everything else.

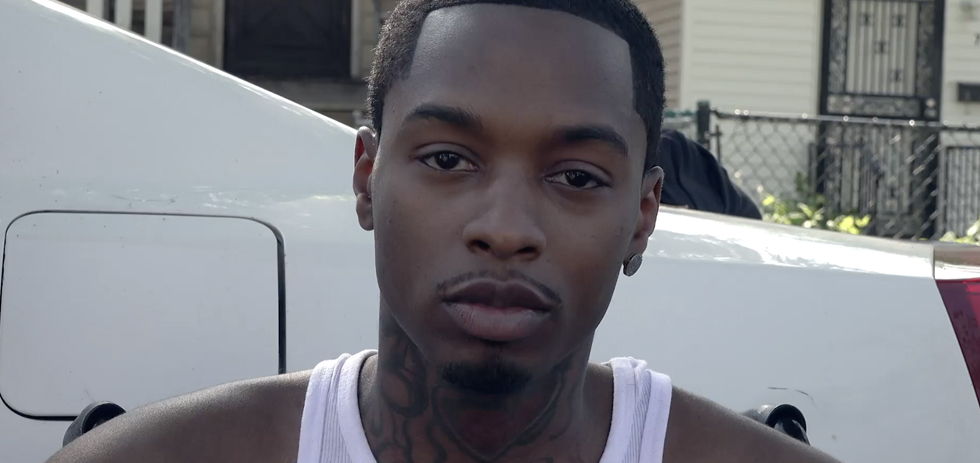

My original idea, because of Denzell’s story, was that I’ll find a couple of people who’ve been shot and nearly died like he did in Miami, and that’s how the story will begin. One person that the people in my apartment block knew was Solja… and you’ve met Solja in the film.

Yeah, right at the start of the film.

And everyone asked me, “George, how long did it take you to get their trust?” The truth is it takes about 15 minutes because in a … when people are in a gangster environment like that, where they’re being shot at all the time, they have to learn to assess a cop or another gang member or anyone, particularly a stranger, in minutes because their life can depend on it. Within 15 minutes, we shot some of the most important interviews in the film, within 15 minutes of meeting Solja. And we’re still friends with him.

That plays out in the documentary, in entering a space where a sense of trust functions as a means of survival. That comes through in these early, direct and honest moments… and when this all takes place in the documentary, they haven’t known you more than an hour?

Well, we never got anything better, and it’s in that first interview that he says, “It was just like that angel girl, the model girl.” And suddenly my ears pricked because Denzell had gotten me thinking about the supernatural element, the white light thing, and here was this famous model they’re telling about who they believe, they sincerely believe, that she hasn’t left this world completely. She comes and warns them about other gangs and police and … that she’s like their guardian angel. At that point I did not have a film, but then when I … this is like the first meeting, when I heard about Kaylyn I thought, “This is a great story.” I knew that if I could find, if her father could talk to me, if her sister would talk to me, I could make a film where she was the connecting link to everyone in the community.

She wasn’t a gangster. She was an innocent victim with a possible future, and incredibly beautiful and a great loss to the world. She was brilliant academically – she was from May Block which you know, we see her grandma’s house, we see where she’s killed – but she had that kind of potential, some thought, to become president someday. Michelle Obama lived in that neighbourhood. She was a track runner, she was going to be able to go to college as well as get a modelling thing. She was an incredibly talented, aspiring person.

And this is the factor shifts White Light beyond that initial focus of ‘people who nearly died’ and includes those who have – and those this death has affected.

Picasso said “I don’t seek, I find.” I find with all of my films, like with Snow Monkey, it was when I found the ice cream boys, the vendors. Then I realised, “Okay, this is going to be about young boys, and I now have to find some gangster boys and some kuchi [or kochi, referring to the group of Pashtun nomads] boys,” and then there’s these three groups of boys. At that moment when you make that decision, you don’t know if you’ll discover that the family of Kaylyn don’t want you to make the film or something like that. When you find out that the family are okay and that everyone’s happy to talk, then it becomes more like a drama or something in that as an experienced documentary maker, you know what you’ve got to try and capture.

You know that you’ve got to get the father’s story of when you heard about her death. You’ve got to – and I knew I would not have a film unless I could – find the boy that was shot with Kaylyn, because the news reports were saying that he was the intended target, although he wasn’t. That’s lovely John John. He was so shattered by this experience, of Kaylyn being killed. He was shot with a few bullets and she only got one, and hers wasn’t fatal. And the ambulance said “We’re taking you first” and he said “No, take her” and they said “If we take her, you’ll die and the ambulance can only take one person at a time.” And he said “No, take her.” He really is a hero. But because the media said that he was persona non grata, and everyone believes the media, he went into hiding. It ruined his life, he stopped going to school and everything. Not even the gang would tell me who it was.

I knew I had to have him as a key character. And then one day there’s this lovely young boy carrying Solja down to our car. Because Solja’s lost a leg, sitting next to him I noticed a bit of gauze on his stomach, which I knew that would be a colostomy bag. I thought “this kid’s been shot in the stomach.” It takes place in real time where he decides to let me know he was the one that was shot with Kaylyn. He’d never done an interview, he’d never let anyone know. We had a dash cam, one of our cameras attached to the dash of the car, that was rolling. So that’s real time, you know. It was actually when he revealed that to me in the film. It’s not something that we reconstructed.

In fact, there’s almost nothing in that film that’s being constructed. Everything is really old-fashioned, traditional cinema verite. And so that moment, that day when I knew I’d found John John, I knew this film was meant to be. In a way, Kaylyn was helping us as well, because his story is so important to the film. And then Father Pfleger, you know, with his campaign to end guns I thought, “Oh, this guy’s a bit of a do-gooder,” and then I discovered that his own son had been killed and then it became different. But I held back the revelation of that until later in the film when he says “I almost lost faith in God, so what do you do?” And then suddenly he’s saying, “We’re going to go out, we’re going to take [the] Dan Ryan [Bridge].” So then his son being killed made him a militant activist against guns and violence.

I was constantly puzzling about how I was going to show the contrast between the very safe white city of Chicago, like, there’s almost no killings in Chicago city where the white people are, and we decided on the boat ride, it took about five half-days out on boats to get all that footage… and we held it until the end. But I think it’s the most powerful thing in the film where suddenly you see Mac and Dave looking out on a world that just seemed impossible to them, where the cops are relaxed and everyone’s laid back and like, you know, the other world. The world that they never get to go to, you know?

It’s a scenario that carries across so many American cities, even in the name ‘south side’ as something that appears again and again in these historically (and in many cases, presently) heavily segregated major cities.

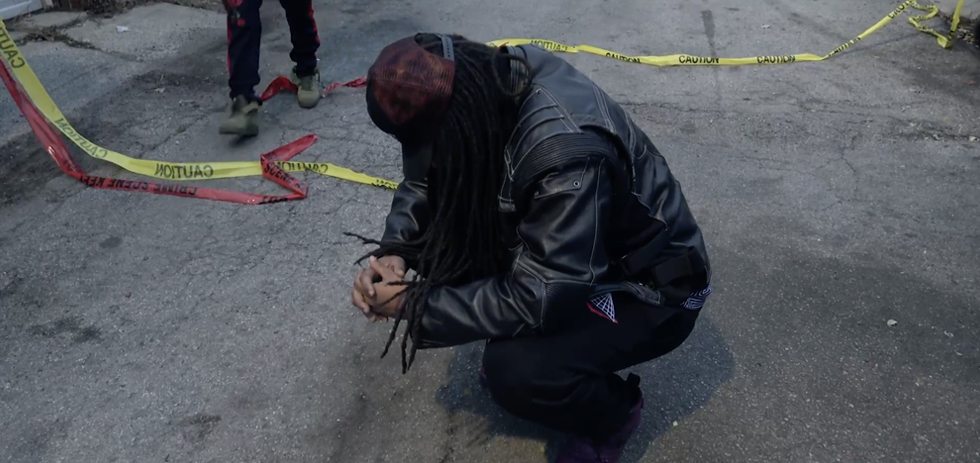

Well, it’s in Pittsburgh, it’s in a lot of other cities. There are cities with worse statistics than Chicago, like St. Louis, but Chicago is historic in its … they call it Chi-Raq because there’s more people killed there [than US soldiers in Iraq]. When we were there, when you’re there you know … things happen and you don’t get them, and they happen around you. Like, we’ll be down interviewing Father Pfleger and come back and find that four people have been shot in front of our apartment and there’s only crime scene tape and they’re gone, you know what I mean? There were shootings and things happening all the time, and I often … personally, I think “My god George, you missed a lot of stuff.” But you can’t be everywhere. But Waqar and I have worked together now for 12 years. Waqar shot Miscreants of Taliwood with me, Love City, Snow Monkey, the virtual reality films, all the Pashto dramas and this. We both love the art of cinematography.

The scene that opens the film with the people saying a prayer on the street corner, we’ve cut this out of the film now but that was Albert’s Church. You know, Albert’s … the guy who loses his three sons. His three sons are killed. We’re driving along with him and suddenly he says “There’s my church.” And we’re off doing something else. I said, “Okay, let’s stop.” And we get out and we filmed … and that’s a wonderful way to begin the film.

Right, it was happening when you were just passing by?

We were going with Albert for him to tell the story of one of his sons, you know, the three sons are killed. And he said “That’s my church. That’s my actual church.” We stopped and we went over and we had that in the film, him saying “That’s my church,” but that’s one of the things we had to cut out. You don’t need it. You don’t need to know that. But everything is, in reality, everything is extremely linked.

There was a version of White Light that you screened at the Sydney Film Festival as a ‘preview’, but there are some fairly major changes between that version and the one that screened a couple of months later at Melbourne International Film Festival (MIFF)?

I shot the film with the structure that is in the MIFF version and not the Sydney version. And then when I came back, the people who looked at the film – Screen Australia and other people – said “No, we can’t see the dramatic arc.”

I said “What do you mean?” And they all said “No, the dramatic arc would be where you have, you meet everyone then you get to know the middles of their stories all together and then all their climaxes to their stories happen at the end.” In the Sydney version, you’ve got John John going to get his colostomy bag off and learn nursing, you’ve got [Lil’] Mac and Dave being photographed by Chantal and they’re talking about their future. You’ve got all the conclusions. You’ve got the ‘Mario, Make Me A Model’ event happening at the end.

This was following what everyone told me that I was stupid, but more or less told me I was stupid that I’d made a film without a proper, it’s this new thing where you’re supposed to conform to the idea of a dramatic arc and that’s the way they saw it. I was made to feel so insecure by these, this idea that I was stupid, not making a proper dramatic arc, that Peter and I recut our footage. We take the Mario Make Me a Model scene … originally, we had them both together as they now are, where you see, you meet Mario, he talks about Kaylyn, and then you see the gang going to the event and that’s quite early in the film. We cut that out and we put that at the end. So we put all the things that with the ends of stories at the end, all the things in the middle of the stories in the middle, and all the things.

For me, I sat back and I watched it at the Sydney Film Festival and I thought, “you know, this film could have a lot more dramatic impact and be easier for people to understand if I went back to the original.” And then it was interesting. When I went back to the original, which is the current version, immediately American distributors, Event Cinemas who were screening it in Australia, everyone who’d seen the Sydney version and were not wild about it were suddenly wild about it. I got like “ah, it’s pretty good George,” you know, like “Not your best, but a good film” up in Sydney. When I recut it for MIFF, I got wildly ecstatic support everywhere, from everywhere. And this is quite often people who’d already seen the Sydney version, and some people had virtually dismissed the film based on the Sydney version.

The change was largely a structural one, but the film does have a different flow in the current cut. I think cutting and returning to the same scenes in the previous cut felt like it was seeking a particular emotional response towards the end of the film.

I changed it completely structurally. If you look at the two, what it was I got all these characters. So now the whole of Kaylyn’s story ends and you get to know John John and the people relating to it, and then it moves on to Albert and then Pfleger and then the end so that people are not broken up and so you get to know and like people. I discovered when they were broken up, [they’re] too broken up for you to really get involved with them properly. I find that if you look at all my films, they have obviously, you know, all my films people have liked them and they’ve succeeded, but they haven’t got this … easy to understand sense of a dramatic arc. They’ve got a kind of me feeling it emotionally and feeling what the dramatic arc is for me. But it’s not logical. It’s not that kind of “let’s put all the beginning bits together, all the middle bits together and all the climax bits together,” you know?

In the new version the most important section for me is with Father Pfleger… and it’s the way it was originally and the sheriffs say all these young people, they see them as gang bangers but they’d love to have a different kind of life. So now you see Mac and Dave with Chantal and they’re saying how they’d like to be clothing designers and cooks and things, and you see Lil Dave getting his diploma and that very human side of it. You see Solja and Tia together in love, and you see Mac with his girlfriend. So suddenly there’s this wonderful, humanising thing of them not as gangsters, and that … before those things were all there but they were spread through the film so that you didn’t connect them properly and get to grow and like and love the characters.

With Snow Monkey it was the same. I had the same sort of thing where you’d have a good section on Steel and the gang and you’d get to know him, and you’d have a good section on the ‘Ghost Busters’, a good section on the Ice Cream Boys, and then they’d start to come together. And that’s how this is too. When you suddenly see Kaylyn’s father Allen at Pfleger’s rally and they hug each other, the story’s united but you’ve really gotten to know Pfleger and you’ve really gotten to know Allen.

Yeah.

And so that’s where it was. I think in my long career, for the first time I let other people make me lose my nerve and try to make it conform to a contemporary idea of a dramatic curve.

It feels like it’s cut in a way that reflects the kind of uncertainty of the characters as well where the atmosphere is shifting at a rapid pace, where the audience is positioned within this precariousness experienced by these figures.

In dramas, people tend to have to conform to certain characters and remain consistent, but human beings are not that consistent. To see Head Shot one minute saying how “I don’t even believe in God” and this and that, and then seeing him with his baby on his chest and admitting that he’d like to learn to use a movie camera, and having his white wife Sharon talking about it, gives it a, gives him a complexity. And it’s with, like that with all of them. Like Dave particularly, where you see him doing those hard raps in front of the store with Lil Mac and they’re guarding the store, but then you learn that he’d really rather be a chef, and he’s a pretty sensitive rapper, and Mac would like to be a clothing designer or anything artistic.

It sort of also amplifies the point, where there’s this existing structure and community where these people and characters are growing up with their own ambitions and trajectories… and White Light focuses on the systemic structures that function to impede all of this.

All of them have ambitions. And the thing for me as an artist, I find always throughout history, the African-American community has a greater proportion of people who love the arts and who are artistic than any other part of the American community. So you’ve got all your great rappers and jazz musicians and painters and dancers and they’re … so me as an artist, the lovely thing for me was for the first time in this film, I’ve used the portraits I’ve done of all the characters to tag them at the beginning. And what’s beautiful is, growing up in … with art theory, when I was young the idea was “make etchings and prints so that ordinary people can afford to buy the art.” Now, I’ve never been one for making art which is an investment item, you know?

I’ve always thought “My art is public art, it’s for the world.” Most people wouldn’t want to have my paintings on their walls. But these guys don’t even have houses. They’ve got nothing. Most of them couch surf. Solja, because of his disabilities, had a government house and most of the gang was sleeping on the floor and so on. And they don’t have homes to go to. And Waqar and I realised this so we bought some beds and set them up in there so at least they weren’t sleeping on the floors. They were incredibly grateful. But so they would have no place, if you gave them a work of art, right, to put it. No permanent place.

But what I discovered was as soon as I did one of these portraits, one, they trusted me more because I was exposing myself as an artist. But they immediately photographed it and put it on their phone, and their house is their phone. Their social media, everything, so … then they send it out to all their friends and then they meet someone and say “Hey look, here’s the portrait of me” and it’s on their phone. That’s the only thing of value that they own is the phone. And so it’s beautiful. They didn’t say “Oh, can we have it?” Because they’d have nowhere to put it, but I was just delighted.

I did Dave first, everyone else wanted one. And now I still owe a few of them, you know? I’ve done Smiley, I’ve done Chantal, Solja’s, I’ll do Tia, Solja’s girlfriend, when I get back. She wants one but she’s never been dressed up enough. She wants to be really well dressed up, she wants to get her hair done and whatever and she’s never got her act together so I haven’t done her yet. But I’ve pretty well done everyone else and they loved it.

Anyway, on this recent trip back we had beautiful prints made on coloured paper, on high-quality art paper, of all their portraits and we got them framed. And now you’ll see on all their social media and their raps and that, they’re terribly delighted. You’ve got Lil Mac rapping and there behind him is his portrait from me, and he’s the proudest person on earth, you know?

There’s plenty of documentaries and radio hours on Englewood and South Side Chicago, and a fair number of articles online written on the area. One of the most recurring trends is the reporter, writer or filmmaker behind the piece embedding with police. Whether it’s taking a drive through Englewood narrated by the cop escorting them through the area, or whether it’s accessing the police as the first source for a local crime story. Your documentary takes a different approach, capturing the degree to which the police are frequently perceived as a greater threat than other gangs,

We did go and see the police commissioner, Eddie Dixon, who’s black but not … not beloved. And he would not assist us, nor none of the police would assist us. I actually thought that had I been able to, and the detective who investigated Kaylyn’s murder, he would have liked to have been interviewed, but they wouldn’t let him be interviewed. And the reason is that only one in 10 murders are caught… 9 out of 10 murders go unpunished. And this is terrible… the families still feel unsafe, everyone feels unsafe. And so naturally, the police don’t want anyone revealing their failure.

I know that you had an encounter with them while filming?

It was a totally unplanned thing in the film, on the day I took Solja to court and he learnt that he had to go to jail but it was also his birthday.

And so I went back to … he had his ankle bracelet on but because it was the court day he had movement. You know, normally he’s stuck inside, he’s not allowed to go outside his apartment. He’s got a police bracelet on his ankle that monitors his movements. And this was just to share the day of his birthday with the gang and suddenly the cops turned up. And that normally, that would be a terrible thing, but the day of the police bust is one of the best moments in the film. The cops did me a favour. As long as they didn’t break or confiscate my cameras, it was wonderful. And then there’s a really interesting new development in documentary making and that’s because now that everyone’s got mobile phones with cameras on them, you can go back in time so that you know that if you’re interviewing Sharon about being shot, you say “Well, did anyone film that?” She says, “Oh yes, a guy passing in the car. I’ve got that, I’ve got that film.” And so in the past, you’d just have someone talking about something that happened, but we accessed all that. So now there’s a new job for documentary makers where we’ve got to make sure that we know whether there’s any security cameras. Like, the film wouldn’t work nearly as well if we didn’t have the security camera footage of Solja being shot, and later the store being shot up again at the end of the film. And you know, Al, the guy that gets beaten up by the cops, he’s talking about it and you see him getting beaten up by the cops.

Susan Sontag said the problem with documentary makers and photographers is that it’s selective and it’s not the images of the people, but that era is past now. The people have usually filmed these things themselves. A lot of the news footage you watch on TV, if it’s … a lot of the best footage that came out of Egypt during the Jasmine Revolution was people filming it on their mobile phones. It’s no longer the big movie camera that’s important, it’s the one that captures the moment when the gunshots are fired or the riot happens. And so that’s a new thing we’ve got to do. It’s an obligation now. Filmmakers working in documentary in those extreme situations, you’ve got to seek out and find … it’s quite often hard, because a store like the one where Solja was shot, they get rid of all the footage after a few months. The cameras roll and roll and roll and then they wipe it all.

And then kind of like the Instagram kind of, or Facebook stories.

Yeah, they’ve all got that stuff. And you discover that people like Solja, that’s so empowering. He’s more or less running his own TV station, live streaming everything all the time. And when they do their raps, they film them and they’ve got a huge audience amongst their own gang and the people who follow them. And they’re disseminating their own news. They’re like Channel 9 but on an intimate scale. It’s amazing. And once again, it’s our obligation to find out if there’s any of that that we can use in the film.

So you see Sharon talking about “Head Shot’s the father of my baby” and then suddenly you’ve got her telephone footage of Head Shot the moment the baby was born with little DJ on his chest.

Like in the case of Kaylyn, she’s an incredibly high-profile person, she’s murdered, and I do know that there are three people in the car that killed, shot Kaylyn, and I do know that two of them have been killed by the opposing gang. But I can’t say that or we’d get them in jail, you know? There’s an investigative side to what I do that… I cannot, I can write about in a book someday but I can’t put in the film or these guys go to jail. I’ve had to get Carolyn Virtue, who’s a film lawyer, to go through, and other people to go through and make sure I’m not putting anyone in jail.

There’s a lot of stuff that’s opportunistic that I could have used in the film, but it would have been ethically wrong to do it because I would have betrayed the people who through their naivete have said and done things on camera that would put them in jail. There were limits to what I could do ethically in terms of … these guys trusted me to know what I could film without getting them in trouble, and if I’d broken their trust then it would have been a terrible breach of respect for them.

I feel like there’s also that immediate assessment of whether you’re someone to trust that gets made, and that if there’s a reliance on a clear judgement of character to survive, those in the documentary have made the assessment –

I wouldn’t hurt them. And that’s interesting. Smiley who, one of the big decisions on the film was to get Smiley to be the narrator, so he’s the voice of the film. And he’s also the supreme gang leader, and so recently we took the film back and showed it to Smiley and I was very nervous because if Smiley had said “George, you can’t have this or that” and it was something that was structurally important to the film then I’d find it, I’d have to do a recut and the film would probably be a weaker film.

It was interesting, the places when I was trying to read his emotions while he was looking at it. He had his partner with him, his girlfriend, and I was thinking “Well, this is not good.” But in the end, he came and said “There’s only one thing,” and that was we did not mask the faces of the dead people on the streets. You see dead bodies on the streets and he felt that that would be painful for the families to see their faces. And I said “All right, Smiley. I’ll find a solution for that.” And that afternoon I went for a walk and someone had recently been killed on a corner near my house and the family had come and cut out a little wooden heart like the one you see at the beginning of the film, and put a gold bar above it. And I came back and I said, “Smiley, what if I put hearts over their faces?” And he said “The families would love that.” And then everyone’s loved that.

And it’s being shown, screened and screened and screened, and they’re amazed that anyone’s done it. So that’s ultimately the best. Just like when we were in Afghanistan, the best work we do is making Pashto films that help change attitudes in Afghanistan. We can make a documentary about making those films, and it can be shown at Sydney and Melbourne film festivals, on TV and stuff here, and people will find it interesting, but the actual films we make in Pashto language in Afghanistan and show there really do bring about social change, whereas our documentaries won’t.

And people can see the documentaries here, but they’re probably not going to be able to make life better for women in Afghanistan, for example. Like, it’s great for people here to be aware of what our films make them aware of, but it’s not really going to impact anyone over there. It might inspire someone like you to go over and work there, but it’s not going to change our attitude about politicians or anything. But … over there, for example, with the Pashto films made in their own language, only 2% of the population is literate so you can’t have subtitles. If we showed us … our documentary in Afghanistan, we do show it to everyone who can read. Even if we have the subtitles in Arabic, they still can’t read it, you know? So the only solution to make films in Afghanistan is to make them entirely in Pashto and within their cultural limits, and then those films are uninteresting here because they’re totally culturally different.

On cultural differences, the manifestations of religion we see in the film, particularly in Father Pfleger’s actions and church services, feel distant from how Christianity is often seen in an Australian context – there’s these cathartic moments in the church and others where it operates with far closer proximity to activism than it commonly does in Australia. What were your impressions of Pfleger and religion in the area?

We’ve never had a church like that. They virtually don’t mention Jesus but you realise that, I think if I really got to know Pfleger, you discover that he believes in an abstract sort of animistic God and not really the Bible, you know what I mean? He’s a humanist, and the church is a way of him being an activist and having … I don’t know how many times he’s been threatened with expulsion, excommunication. None of the bishops like him. And he’s like a performance artist. When he decided he was going to take the Dan Ryan, well that’s the main artery of American highway. I thought, “You’re mad.” Personally, even me who does mad things thought it was mad. I thought, “You’re just bragging, you’re not really going to do that.” And the next minute he’s on the phone saying “Hey George, are you coming? We’re all going to be at such-and-such at 7:00 a.m. tomorrow morning.” And I couldn’t believe it. He did it. You know that … and there are hundreds of cops with dogs and bikes and everything to try and stop them, and they did it. It’s amazing.

And for me as an Australian, it was one of the most wonderful moments of my life. I originally went to America in 1968, which is the year that Martin Luther King was killed, and one of the reasons for making this film was … 2018 was the 50th anniversary of King’s death. And we filmed, we went to Memphis. And backed in ’68, ’69, I worked with the American Civil Rights Movement, so my history goes back that far. And I felt that I’d love to be working in Yemen, I should be working in Yemen, but this is the 50th anniversary of King’s death. I’ve got to be working in America. So that was my deepest motivation for making this film, and that nothing has changed. That King would be … towards the end of his life he was depressed anyway. He was saying that nothing was changing. But it’s gone seriously backwards. It hasn’t gone forward.

Yeah, his writings towards the end of his life have this very determined yet maudlin tone.

Oh, he’s very depressed towards the end of his life. He almost knew that he was going to die, you know? He said, “I won’t make it to the mountaintop with you,” you know?

Yeah.

Like, my history was … I was working with Joe Delaney in New York. I helped cover the Civil Rights Movement. I was only 19. And an album came out. I’d love to get it, a vinyl album came out of all the speeches, King’s greatest speeches. And when other people were playing The Beatles and The Rolling Stones, we were playing that. It was just so inspirational. I can remember sitting and doing Joe Delaney’s portrait while playing, Martin Luther King doing the “I have a dream” speech on LP. And then I wrote “I have a dream” on the canvas.

But one of the greatest moments, and always will be in my life, the thing that makes making documentaries worth it, is this moment where I was delighted to see Jesse Jackson turn up, this old man with Alzheimer’s who marched with Martin. So I was delighted to turn up, I was delighted to arrive at the Dan Ryan, one of the greatest moments of my life. Here’s Jesse Jackson, who’d marched with Martin Luther King, and my new hero Pfleger, and the father of the subject of my film, Kaylyn, Kaylyn’s father Allan. And there was this moment where the police and bodyguards and everything else, where I was an arm’s length away from Jesse Jackson and Pfleger as they broke through the police lines.

And I’m there, this George Gittoes from Rockdale, Australia, I’m on camera and there’s cops and everyone trying to stop everything from happening and no one touched me, you know? And I’m just sort of walking backwards and I’ve got that historic moment, and a shudder went through me. It was like, one of those great moments you see in old black-and-white footage. I was a 19-year-old again back in the Civil Rights Movement. But back in those days I just had a lousy little black-and-white Pentax camera that could just click a few things. Here I was rolling 4K and Jesse Jackson’s walking into my footsteps as I’m walking backwards with the camera. This was such a great moment. And as a filmmaker, I’m so lucky. I’ve got Waqar and we’ve worked together for 12 years. And I always know that we, on that day, he worked one side of the march and I’d do the other. And we don’t work together, we don’t have any communication. But I just knew that he would know to come together. And so he’s on the left at that moment, and he could have been anywhere in the crowd but we coordinate just sort of almost telepathically. Suddenly out of the blue, Allan, Kaylyn’s dad, appears. I didn’t know he, I didn’t place him there.

Yeah, I remember this moment.

Yeah, and suddenly Pfleger says “Oh, here’s the father of the model who was killed,” who’s the subject of my film, and we got it. So that’s why I believe so much in this old-fashioned principle of cinema verite, you know? Like, you can’t say “Hey, can you do that again Allan? Can you ask Jesse Jackson to just back up three metres? We missed that shot where he put his arm around you.” You’ve got to get it. And that’s why I love documentary making. Like, I was a generation back in the 70s where almost no one knew how to use a camera. Like, Andy Warhol showed me how to use a camera in America, a movie camera. And people said “George, why don’t you make dramas? Move to feature films?” but the reason why I’ve always loved documentaries is this unpredictable thing. It’s like sports. You don’t know whether you’re going to win or lose. You really don’t. You could miss that moment. And then the days when you do get that moment is the greatest. You’re really ecstatic. You’re high. That’s fantastic when it comes together like that.

It seems like there’s a lot still in store for this movie, because it’s not even getting a theatrical release here till February, and you’ve got to go overseas and everything.

Event Cinemas are doing a theatrical release in February, and we’re going to bring Smiley out for it. It goes to Brisbane and we’ve only now just finished it enough. We’ve entered it in South by Southwest. I always get my films at IDFA and Berlin. We’ve had it confirmed that the Czech Film Festival’s taking it, and so Syracuse, we’re screening it in Salem when the artwork goes up. So yeah, it’s … only just, it’s very, very fresh.

My role is to show that Australians care about places like Yemen and Afghanistan. That’s what I do. That’s what I had been doing for the last 40 years. And so I’m going to go on doing that, so I’m hoping, you know, to get back to Yemen. What’s happening there is terrible. And I’m reactive and I’m in this fortunate position as a painter, where I can go to people who believe in my films and I can say “Hey, buy a painting for 30 or 40 or $50,000” and I don’t have to go to a funding body. And that’s the wonderful thing, and that’s also the thing that keeps the Yellow House going in Afghanistan. Next Monday I’m delivering, you know, the big ceramic teapot that’s out in front of our house. Someone who loves my films says “Hey George, I know you want to go and shoot some footage in Yemen. We’ll buy that pot.” So they’re paying $16,000 for that pot that’s out. And they don’t really need the pot, but the pot’s worth $16,000 so they want to resell it, and they’re helping the film, you know? So I’m, I know that I’m in a very, very lucky position that if tomorrow I felt that the war was breaking out between Iran and America and Saudi Arabia and involving Yemen I would be there in a flash. But I wouldn’t have to go to Screen Australia or the ABC.

And one of the problems with my films is they’re so dangerous that I can’t get insurance and everyone requires you to have insurance. So there’s nowhere in the world the ABC would do a presale on White Light. The idea … no insurance company in the world would cover me and Waqar to work in south side Chicago with the people we work with. And the same with if we go into Yemen. But I’d be probably the only person in the world who could work there and the only person in the world who could work the way I work in Yemen, because I’ve lived and worked there and had exhibitions there and know the people.

You’ve shot in Yemen?

Yeah, well Yemen coincides with my landmine period where I was making films and documenting landmine victims. I had a big show of my work on landmines at the United Nations in Geneva. I was invited by the Yemeni government to go and work in Yemen, so I’ve got massive contacts and friends throughout the whole country.

Was this after the 1994 Yemeni Civil War?

Yeah, that was at the time of the (USS) Cole, when the Cole American destroyer was attacked and bombs lit off and put a big hole in the American ship by Al-Qaeda. And you know, when I was in Yemen I got to spend time with every side from Al-Qaeda to the … and so I feel like the problem for me is that the lifetime of work that I’ve done gives me a level of access which no one else has got, no one that I know of has got, and even though I’m 70 years old it makes me feel obligated to continue working because I see the news, I know that it’s wrong.

And the funny thing for me is that I watch things. Like recently we watched Deep State, it was a TV series called Deep State where you’ve got people working with the CIA and these companies that make, profiteer from war, American companies and so they actually now create the wars. It’s this thing of a thing. And I can watch these things and I just know, “That’s impossible,” you know? But no one else would know that, that this is ridiculous. Whoever wrote that script is nuts, you know? Because I’m actually, even though I’ve never carried a gun, I’ve never hurt anyone, I’ve never punched anyone, I’ve never done anything violent, I see all this violence and I really do know what it’s like at the frontline of a war. And the way I see it portrayed constantly in television dramas is often very, very ridiculous.

So it’s funny. It’s like, I’m an ex-tennis playing watching Wimbledon and maybe I’ve had a game at Wimbledon, I know what it’s like, it’s a different kind of experience to someone who just likes watching tennis. And so yeah, like for example with Deep State, we’ll often be driving along. The drive from Kabul to Jalalabad is incredibly dangerous. And in this, there’s some Americans and they’re in a van and then four or five trucks come behind them, utility trucks with guys with rocket launchers and AK-47s. And being Americans, they roll down the windows with their handguns and start shooting back at these trucks. Now, no one would do that. You’d have to be nuts. The truck’s a four-wheel drive, they’re in a van, but “that’s what Americans do.” But in reality, no one would be stupid enough to do that. But if you’re just watching it, you’ve never been into a war zone, you’ll kind of accept it, you know what I mean? But no, it’s just totally impossible. It just would be nuts.

So we’ll often be driving along and a whole lot of ferocious-looking, armed people will come up and stop us and want to get us out. And I’ll walk out and I’ll walk over to the nearest person and hug them and be nice to them, offer them a banana if I’ve got a bunch of bananas. And I’ll use my empathy factor. And it was funny. When I had the retrospective of my films at the Museum of Contemporary Art, the audience at the Q&A did not know that there were several special forces soldiers who’ve since become like mercenary security people in wars around the world. And these guys know me. They’ve been with me in places like Rwanda, not just by coincidence, you know? They’ve seen how I operate.

And some very naïve arty people were asking all these typical questions. One of these big special forces soldiers just took over. He could see that I was finding it difficult to answer. And he said, “You’ve got to understand, it’s the hug factor.” “The hug factor,” yeah. We just don’t know how he does it. That George goes over there and there’ll be a guy with an AK-47 pointed at his head and George will just give him a big hug. And then he gets back in his car and they drive off. And you know, because those guys could never do that because all their training is to be weaponized, and it just astonishes them that I get away with what I get away with.

It’s empathy. It’s just being able to read people. So with Solja and Mac and that, when we first went into that room, Solja’s there in his wheelchair and it seems funny now, but there’s Lil Dave and Boozy and John John and these others that I now just see as soft teenage boys. But when we first walked in I was the first white man that had ever walked into their apartment. It was like cats that put their fur up when a dog walks into the room. They all put on their nastiest face, their most terrifying face. I was completely relaxed and when they realised how relaxed I was and I made a few jokes, they all calmed down and I realised again something I’ve realised many times in my career, which is that fear is a form of judgement Even though they might have put their fur up, if you show fear then it’s letting them know that you think they’re bad people, that they could kill you. And they could kill you, too. But if you show it, you’re sort of making a judgement on them.

When I was documenting the massacre in Kibeho in Rwanda, thousands of people were being killed all around me. The RPA leader, the bad guy that was heading the massacre, came over to me and said, “George, if you even think of taking a photograph,” because he knew my photographs could be used, as they were, against them as war criminals, “We will kill you. If you even think of taking one.”

So I took a couple of thousand photographs, and at some point he directed the guy to go over and kill me. And I looked at this guy who I’d seen chopping the heads off of children and I thought, “How am I going to survive this?” And I noticed that he had this beautifully made utility vest holding all of his ammunition and guns and knives and things. It was hand-made. And as he’s walking up to him I said “That’s beautiful,” and I put my hand out and I touched the fabric and I said “Where did you get that made?” I said, “I could really use that. I mean, I need something. Look at all my cameras and my films and everything. I need something to put them in. That’s just so good.”

And the guy who’d been sent over to kill me said “My mother-in-law in Kigali makes these.” And so I said, “Can I get her number now next time I’m back in Kigali? I’m going to get her to make me one.” So this guy’s not going to kill the bloke that’s going to go and be a patron of his mother-in-law. But also, he’s looking me in the eye and he knows that I’ve seen him killing people. And you watch an American movie like, there’s that one with DiCaprio, Blood Diamond, and there’s your typical American journalist in that and when this journalist, this woman journalist sees some bad things happen she feels that she’s got to ethically go out and abuse the people that do it. Well I know, just like the scene with the trucks with guns following the car, that in that situation the worst thing she could have done would have been to go and tell these guys that they’re monsters. They would have killed her instantly. And you just can’t do that in the field.

So yeah, the whole judgement thing. So even this guy that’s been killing children in Kibeho, he’s got a family. He’s got a mother-in-law back in Kigali. He’ll probably never forgive himself, but he does have a soul. And if he’s hot on blood lust and he can see a pair of eyes that are judging him and things that are being said to him with judgement, he’s going to put that person out. He’s going to kill them. So these are the skills that you pick up in a lifetime and it’s what keeps George Gittoes alive.

Yeah. Wow. I think that’s probably a great way to wrap up the interview. I think that we went for … that was a good 90 minutes.

Well there you go. Would you like another cup of tea?